A Playful Tree for Fall

Fieldnotes for November – December 2025

by Kay Broome

Horse Chestnut Wreath (Web photo: Lobacheva Ina)

Kids love Halloween, dressing up as some scary monster: a goblin, vampire, werewolf, and still popular – the stereotypical witch. Childhood can be scary and for once, kids can wear a costume and be fearsome or courageous, or whatever they wish. I believe that at its core, Halloween and its earlier precursors were originally dress rehearsals for our own demise. We all fear the uncertainty of death and in past times, death was more frequent and often came sooner than expected. Dressing up as fearsome beings may have originated as sympathetic magic to keep the monsters of disease, war, famine and other disasters at bay.

Halloween in West Toronto, 2017 (photo: Kay Broome )

From Funeral Feast to Candy Quest

Halloween has its roots mainly in the Celtic festival of Samhain. This holy day of October 31st acknowledged the passage of the harvest and the coming of winter. Samhain was a solemn occasion honouring the dead who had passed during the year. It is believed that in the British Isles, burial mounds were opened and tribute paid to the spirits dwelling within. At Samhain (as well as during that other Celtic celebration, Beltane, held May 1st) it was and still is believed that the veil between this world and the Otherworld is thinner. At these times, we can communicate more easily with the spirits of the dead, as well as with the fairy folk.

Lighting Candles for the Dead at Samhain (Web photo: Freestocks)

The Mexican festival of El Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, is possibly that country’s most famous celebration. Although this event is replete with skeletal symbolism and people wearing skull-face masks or makeup, it is a joyful occasion. There is much merry-making, with offerings made to the ancestors and with families gathering at gravesides, there to feast and celebrate the loved ones who have gone on before. El Dia de los Muertos has indigenous roots with the Aztecs or Toltecs, coupled with an overlay of Spanish Catholicism.

Calaveras or Ceremonial Skulls for El Dia de los Muertos (Web photo: Nick Fewings)

Our own Halloween, with its creepy veneer of ghoulies and goblins, haunted by ghosts and graveyards, is no doubt a syncretic mix of the Samhain of our earlier European ancestors, together with the Christian All Souls’ Day, usually celebrated on November 1st. Halloween has become a fun day of dress-up and trick or treating for candies, chocolates and other goodies. Kids collecting money for UNICEF and other charities for children in less fortunate countries is not sufficient to return Halloween to the more sedate affair of the past. However, modern pagan revivalism has, as much as possible, resurrected older, loftier traditions that honour dead ancestors and acknowledge the end of the harvest and the imminence of winter.

A Modern Day Samhain Procession (Web photo: Robin Canfield)

The Tree that Cosplays

Around the time of Halloween when trees such as maple, oak, aspen and sumac are resplendent with colour, a tall, handsomely shaped tree stands whose palmate leaves are a drab brown, (at least here in Toronto). No matter, North American buckeyes and their European cousin, horse chestnut still offer delightful treasures. When the ripened husks of buckeyes (Aesculus) fall and split open on autumn’s floor, the burnished nuts appear a real treat. However they are in fact, a Halloween trick, for although they closely resemble the fruit of true chestnut (Castanea), they are inedible for most creatures. Only squirrels and chipmunks can safely eat them (although European horse chestnuts are not poisonous for deer or boar).

Horse Chestnuts on the Ground in Fall (Web photo: Georg Eiermann )

Aesculus, the Great Pretender

Like a pre-adolescent kid, the buckeye imitates other trees as if practicing what it wants to become as an adult. The leaves, usually seven-point in horse chestnut and five-point in the American species, are palmate, raying out from the tip of the stem, much like those of papaya. The tree is tall with a rounded crown, somewhat like linden. The deep-throated flowers, growing candelabra-like in masses, are similar to those of the elegant catalpa, but they are smaller.

Buckeye tree, High Park , Toronto (photo: Kay Broome, 2024)

Horse chestnut is so named perhaps because the leaf scar resembles an equine hoofprint, or maybe because the plant was traditionally used as medicine for horses. Most likely transplanted from Turkey to Europe and Britain, the horse chestnut arrived in the US during the 1700s. The flowers are white with yellow throats, the seed casings bright green and spikey. Ironically, horse chestnut is more common in the warmer parts of Canada than are the native buckeyes, the Boreal forest being too cold for North American species.

Horse Chestnut Flowers (Photo: W. Carter, Wikipedia)

Native buckeyes are common throughout much

of the US and the extreme southern edge of Canada’s Carolinian forest. All have palmate leaves with five leaflets, but

they vary in flower color and in fruit.

Yellow or sweet buckeye (A. flava) has pale yellow flowers and a

smooth, beige or brownish shell. The red buckeye (A. pavia) is a very handsome tree

indeed, with pink flowers and a pear-shaped beige shell containing three or

four nuts, in a lighter shade than their cousins.

Left to Right: Flowers of Yellow, Red and Ohio Buckeyes (Photos: Left, Genet; Centre, Dan Keck; Right, H. Zell, Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, a tree that plays around as much as the buckeye cannot help but serve us another trick. Unlike its more well-behaved relatives, the Ohio Buckeye (A. glabra) has a bad habit of emitting a skunky odor when its leaves or stems are crushed. Otherwise, it resembles the yellow buckeye, save the shell is warty rather than smooth.

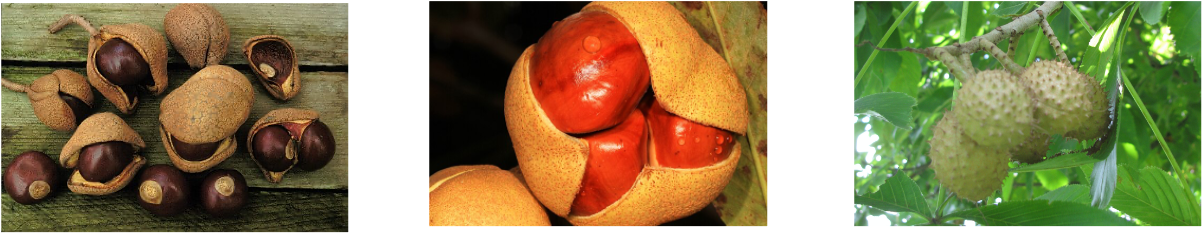

Left to Right, Fruit of Yellow, Red and Ohio buckeyes

Photos: left, Univ. Connecticut Plant Database; centre, Judy Gallagher, Wikimedia commons; Right: Kay Broome, Toronto

When myths and legends were being handed out to the trees, the buckeyes were apparently off playing somewhere, because there are very few if any myths that I was able to find about them. I do recall reading of the benevolent, gift-bringing Christmas witch, Befana, whose effigies were traditionally burned at Epiphany. Horse chestnut branches were seemingly added to the pyre to make it spark and snap. Here again, this species shows its childlike and playful manner.

While working on this blog entry, I noted that there are a dearth of gods who actually depict childhood. There is no end of deities such as Artemis, Brigid, Apollo and Freya who govern the protection of children, but they do not specifically represent this first stage of life. Eros, the Greek god of love, called Cupid in Rome, was often portrayed as a mischievous toddler who enjoys shooting gods and people with his love arrows. But this god doesn’t really do many childlike things other than make life difficult for incompatible people in love. Otherwise, in Greek myths, we do hear of Dionysus being allured with various toys by the Titans so that they could tear him to pieces. We further recall Persephone 'spying a fairer flower' just before she was abducted by Hades. There is also the Egyptian tale of the infant Horus. Here, his mother Isis hid him from his uncle Seti, who had murdered his father Osiris. There is nothing playful at all about these myths, all of them containing a backdrop of dread and danger.

Cupid Complaining to Venus (and stealing honey and being a general nuisance) Lucas Cranach, ca. 1526-27, National Gallery, London, UK

When Childhood Wasn't Fun

Perhaps this shortage of childhood deities is because childhood was never made a big deal about until the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until then, this early stage of life was the means to the end of adulthood, not particularly celebrated for itself or given any consideration as being somehow wholly set apart. There are many reasons for this. Until very recently, say one hundred years ago, children often did not make it to adulthood. Those who survived birth frequently died either from disease, misadventure or, among the poor, malnutrition. And of those children who made it past their third year of life, most would then be lucky to live to see fifty. As a result of all this, families were larger in those days. A women would likely experience seven to ten pregnancies in her life, and would consider herself lucky if half of the children born to her survived to adulthood.

Until recently, poor children worked from a very young age to help put food on the table. In the countryside, peasant children were expected to help their parents with tending livestock and with planting and harvesting. (In fact, this is still a feature with the, sadly, rapidly disappearing family farm. Rural kids are expected to help with the barn “chores”. Of course, with modern technology, they do not work nearly as many hours nor under the harsh conditions of children in earlier times.) Historically, daughters helped mothers to cook, sew, housekeep and tend to younger children. Boys from merchant families were expected to follow in their fathers’ footsteps, often apprenticing at a very early age. The toll of long hours and heavy labour that these children already experienced was only exacerbated with the Industrial Revolution. Increasing mechanization in agriculture and later, in urban industry, led to the loss of jobs for adult workers. Labourers were paid much less and took any work they could find. Moreover, industrial owners preferred child workers as they could pay them less. Due to extreme poverty, children were forced to work even in the mines, where their bodies could wriggle into smaller tunnels. We all are familiar with the chimney sweeps and other child labourers from the horror stories of Charles Dickens and others. And this is not even considering the misery of child sexual slavery.

Illustration of Girl dragging a Coal Tub (Illustration from mid-19th Century, Wikipedia)

Fortunately, in the 1800s there was a massive backlash against this brutality and a general rise in human rights activism. Eventually, after a long and difficult struggle, the Child Labour Laws were gradually changed. By the 1950s, most countries in the west at least, had laws prohibiting children under the age of 16 from working. Interestingly, it was this 1950s generation, the “baby boomers” that were the first who could expect to live better lives, on average, than their parents. This era also brought us the teenager, any adolescent aged thirteen to nineteen. There was, and still is, a great deal of concern as to how this age group is or is not coping.

Although the early indigenous people of North America appear to have for the most part, treated their children well, they too did not consider childhood vastly different from being an adult. Among many First Nations people, children were seen as little people who simply needed to learn how one behaves and cooperates within the tribe. Children were rarely if ever corporeally punished. When they misbehaved, adults would ignore and shun them, or in some cultures, would publicly shame them. In a culture where community is everything, this appears to have usually been enough to discipline a naughty child. There were, of course, adolescent rites of passage for both boys and girls to acknowledge they were old enough to think of marriage and children of their own.

Lakota Doll, ca. 1890, American Indian Museum

Buckeye the Conkerer

In all cultures of the world, children were from birth provided with toys, all of them educational. Buckeyes and horse chestnuts were used the way children today use marbles, as well as for game pieces. Girls made necklaces and toy jewelry from the seeds and boys used them as missiles for their slingshots. The nuts were called “conkers”, no doubt from their tendency to conk you on the head when they fell from the tree. Conkers would be tied to strings and children would strike each other's nut with them saying, “I conquer your conker”. All fun and games, no doubt, until someone loses an eye!

Ohio buckeye nuts littering the ground in High Park, Toronto (Photo: Kay Broome)

This key tells us to not take ourselves too seriously. It is important to take time out to play. Fun activities exercise the mind and the imagination. Buckeye also references friendship, for it is in childhood that we make our first bonds with people outside the family. The buckeyes may not be the most useful of trees, just as kids cannot be expected to help out as much as adults. But these trees are beautiful and their seeds are fun to collect. They provide shade and lots of food for those annoying yet amusing creatures, the squirrels and their relatives the chipmunks.

Chipmunk with Buckeye Nuts (Web Photo Alex Lauzon)

Buckeye instructs us to play. Use your imagination; do what you love and the rest will follow. Upright the rune represents friendship, laughter and loyalty. This key may reference either a sibling or a boy or young lad familiar to the querent. Inverted (or dormant as I now prefer to call upside down keys), suggests the querent may be acting recklessly or childishly. The rune in this position could also warn that you are acting the buffoon or being taken advantage of. Toppled to the left with the flower up, indicates someone who is pompous and takes themselves too seriously. It may also suggest loneliness, or one who is having trouble seeking friendship. To the right, with the flower down, the rune warns of a friendship in trouble, possibly due to disloyalty. Otherwise, it may indicate you are not attentive enough to good friends.

The kennings for the Talking Forest Buckeye are Boy and Marble. The former alludes to the attractive, robust gawkiness of this tree, like an eleven-year-old replete with fart cushion and slingshot. The latter kenning references the use to which the nuts or conkers were put – as marbles for tiddly winks and other games. The Buckeye rune is asymmetrical with a large flower spiral on the right side. Beneath this, are two branches indicating the substantial limbs of this species. The large dot, representing the nut or conker, is shown falling from the right-hand branch. On the upper left is a shorter branch with a bracket on the end, representing the shade that magnanimous buckeye provides.

The Buckeye rune is situated smack dab in the middle of the first grove or group of seven keys in the Talking Forest. This is the grove of childhood. The buckeye is at its height in May and June when the handsome flowers appear, but even more so in the magical, brilliant days of autumn, specifically October and early November – that time so beloved by children, when ghoulies and ghosties are out and the conkers of horse chestnut and other buckeyes are in full display.

Talking Forest Buckeye Rune