Voices in the Summer Wind

Lammas 2024

by Kay Broome

Black Poplar, West Toronto (photo: Kay Broome)

For the second time, this blog arrives at the first week of August and Lammastide. Fall harvest is closing in – the flowers of high summer now becoming fruit – like an idea, voiced at last, becoming the poem, the song, the story. July in Ontario this year has been extremely wet, thanks to climate change, with freakish, massive, almost monsoon-like rain. Generally, it is August that brings the rain and thunder storms here. And that happens, usually, near the end of the month. This is when you most often hear the poplar leaves whispering frantically in the wind. The sound they make on a blustery day recalls the waves on the ocean: calm and soothing. Just before a rainstorm however, their hissing becomes more frenetic: still pleasant, but thrilling, electric, a harbinger of the atmospheric spectacle soon to come.

Poplar Forest In Fehrbellen Wald, Germany (photo: Leonhard Lenz)

I don’t know if poplars grow naturally at crossroads, but I envision them as being the most likely tree to be found at such a place. Their tall, ovoid shapes make a perfect windbreak and the grey-green leaves – shiny and metallic above, dull sage green below – evoke the passage of vehicles, with dust in their wake. Historically, poplars were favoured as windbreaks at roadsides, so they were at least planted at crossroads. These spaces, where two roads meet, are liminal regions, where anything is possible. Many folktales speak of wayfarers meeting the devil at the crossroads, selling their souls in order to gain success in life. However, these modern era legends originate, as many do, from earlier pagan myth.

Divine Messengers

In numerous pantheons, crossroads are sacred to a certain type of deity. Often these are chthonic gods such as Hecate of the Greeks and Baron Samedi of the Vodun faith. Others take the role of the messenger, the go-between of the gods. Crossroads were sacred to the Greek god Hermes. They were sacred also to Legba – like Samedi, a Vodun deity – and to Eleggua from the Santería pantheon.

Hermes attaching his Sandal, Bronze cast by Soyer & Ingé 1834, from Paris Louvre (photo: Nathanael Burton)

Hermes, Messenger of the Olympians

Most of us are familiar with the Greek god Hermes, also called Mercury in ancient Rome. He was the son of the sky god Zeus and the nymph Maia, who was one of the seven Pleiades. We usually envision Hermes as a slender youth with winged sandals and helmet, and the caduceus – a wand or short staff with two serpents wrapped around it. He is messenger to Zeus and to the other gods of Mount Olympus: very quick in his movements, very clever – in fact a bit of a trickster – and not without a sense of humour. Hermes is the god invoked for speed, for eloquence of speech and for success in business. However, like many gods, Hermes has a darker side. He is a psychopomp, a conveyer of the souls of the dead to the Underworld.

Legba, Vodun Opener of the Doorway

An Afro-Caribbean religion, Vodun was brought to Haiti and the southern US by the Fon, Uwe and Aja people of West Africa. In this pantheon, Legba is the messenger god. It is he who is called upon to open the doorway so that the other Loa, the sacred guardians of Vodun, can come through. He is also called upon when one wishes to contact those who have passed the veil of life. Papa Legba characteristically wears a stovepipe or straw hat and carries a cane. His colours are red & black, colours of life and death – appropriate for a mediator between the living and the dead, and between this world and the otherworld. Legba dwells at the crossroads. Like Hermes, he enjoys the company of humans and is very helpful if treated with respect and hospitality. Legba enjoys good quality rum and cigars, which are offerings made to him by his votaries. Here, from the superlative Light in Drk Youtube channel, is an excellent video about Papa Legba and his role in the Vodun religion:

Papa Legba: The Gatekeeper of Vodou and the Keeper of Our Souls:

https://youtu.be/ak1dmIv-MAc?si=P1APYAo7FlfcXCQu

Elegua, Gatekeeper of the Orishas

In the Santería tradition of Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean and the Americas, Elegua is guardian of crossroads. Like Legba, his colours are red and black and he is frequently seen as an old man. But Elegua can also manifest as a young boy. He usually wears a tall, wide-brimmed hat, and carries a large bag and cane, or staff. Remover of obstacles and opener of doorways, Elegua must always be invoked at the beginning of all Santería rituals. The orishas or gods of this pantheon only manifest when Elegua has cleared the way. The following video, from La Corona de Eleggua channel, portrays a “horse”: a devotee of Santería who has taken on the persona of Elegua. Here this orisha’s amiable, trickster personality is clearly illustrated:

Eleggua Bailando (Elegua Dancing):

https://youtu.be/JWZBJhsgjiE?si=iSdNnbw88YtHGMtI

It is easy to see linguistic and iconographic similarities between Legba and Elegua. However, many scholars also believe the Greco-Roman gods share a common source with Vodun and Santería, the latter two religions both originating in West Africa. Hermes, usually imagined as a boy or youth, could also manifest as an elderly man. All three gods act as intermediaries between the deities and their devotees. And all are tricksters, a seemingly common trait for deities who act as go-betweens. All three gods are psychopomps, guiding the spirits of the dead to the afterlife. All are liminal, patrons of the crossroads, standing as links from one world to another.

Aspens in Autumn (photo: John Price)

Poplar's Connections to the Underworld

In Europe, the white poplar and apparently, the aspen, were sacred to Hades, Persephone and other chthonic deities. Perhaps this was due to the trembling of aspen leaves, seemingly in fear. There is also the myth of the Greek hero Heracles wearing a wreath of white poplar on his foray into the underworld, in order to steal Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guarded the gates to Hades' realm. The wreath was to protect Heracles and allow him safe passage back from the land of the dead. As earlier noted, Hermes is equally god of communication and deliverer of souls to the underworld. So perhaps it is not surprising that the tree of whispering leaves was also associated, in Europe at least, with death and the spirits of the departed.

Bronze Relief of Ogma, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, Lee Lawrie, 1939 (photo: Carol Highsmith )

Ogma, God of Letters

Ogmios was a Celtic god of Gaul, often compared to Heracles, as he wore a lion skin and carried a club. A very eloquent and charming speaker, he is pictured as having nine finely wrought gold chains linked from his tongue to the ears of his followers. It is not known for certain what these chains represent: perhaps nine Celtic dialects? The Gaelic Ogma, no doubt a Scots/Irish version of Ogmios, shared his persuasiveness. He is also credited with inventing the Ogham alphabet and runes. One of these runes is Edad, the aspen, or poplar few, which, according to Edred Thorrsson in his Book of Ogham, references the conquering of death. In her book Ogam: Weaving Word Wisdom, Erynn Rowan Laurie associates Edad with, among other things, dreams, enlightenment, and communication with the Sidhe or faery realms. It is interesting to note that this rune alludes to communion with the dead and to otherworldly connections.

Edad – Poplar Ogham Rune

Poplar, The Voice of the Great Spirit

The chthonic association for poplar does not come naturally to me. I imagine the tree primarily as an avatar of language and speech. Certainly, most of our species in Canada possess the noisy leaves peculiar to this species. Indeed, it was held by the indigenous people of the prairies that the Great Spirit spoke through the leaves of cottonwood trees. These trees were thus held in great esteem, and also because they were often the only tree that throve on the Great Plains. Poplar was used in the Sun Dance Ceremony, performed once each year, in late spring or early summer, before the bison hunt.

The myth of White Buffalo Calf Woman tells of how she taught the Lakota people the various rites that were to be performed, in order to keep harmony with Mother Earth and the Great Spirit. One of these was the Sun Dance. A pole made from a stripped cottonwood tree was carried back to a lodge that was specifically built for this ritual. The pole was then planted in the centre of the lodge. Around this axis, members of the tribe would dance, the young hunters taking on an ordeal of propitiation to honour the powerful buffalo totem. Long strips of rawhide, tied to the central pole, would be attached to sharp bone chips pierced into the dancers’ chests. They would then move round the pole, leaning their bodies back and away from the thongs. Other men would have their backs pierced with bone shards. Bison skulls would then be attached by thongs, and they would drag these sacred relics behind them round the pole. Moving from sunup to sundown without stop, without food or drink, the dancers would go into a trance. This ritual around the cottonwood pole was done to honour the buffalo, and to send prayers to the Great Spirit to ensure a successful hunt. Here is a moving video from the Youtube channel, Sacred Wisdom Circle Institute, reconstructing the Sun Dance ritual as it was done in the past.

Native American Sun Dance:

https://youtu.be/qpgzIkgZ7rM?si=XaysSHUJOvpsFDE2

The Tree that Speaks

Poplars are close relatives of the willows, but look nothing like them. Unlike their weeping cousins, poplars tend to be ovoid with upswept branches. Poplars and cottonwoods have thick, leathery triangular leaves, while those of aspen are smaller, round and often crenellated. As they age, poplars develop ridges in their grey bark, losing the smooth cherry-like trunks of their youth. Aspens are an exception, with stark white, lenticeled bark resembling that of European birch. All poplars, save white (Populus alba), hold their leaves on long stems. This attribute is what causes the whispering in the wind unique to this species.

Cottonwoods, West Toronto (photo: Kay Broome)

The poplar tree is the one who talks to us, whispering with the voices of the gods, reciting the poetry of wind, rain and waves. In the Talking Forest, the Poplar rune refers to speech, language and communication. Poplar bestows eloquence and diplomacy.

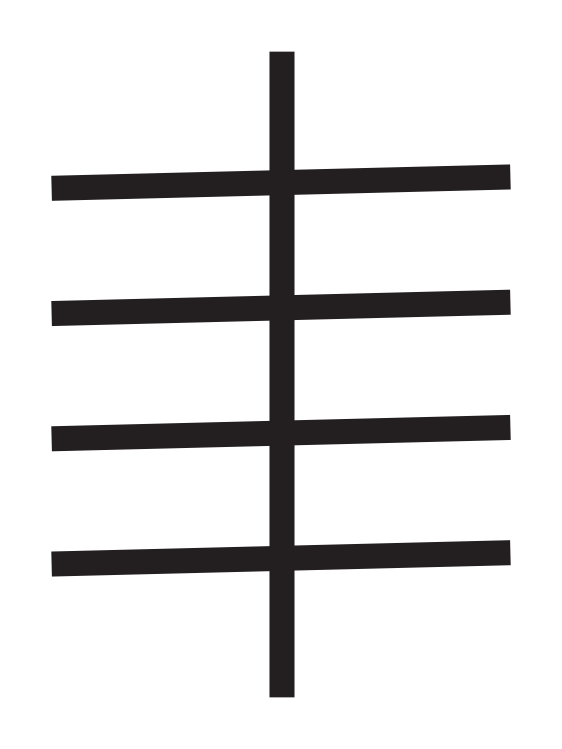

The Poplar rune imitates the shape of this tree. The five upswept branches represent the five vowels in the English language. Poplar is the fifth rune in the Talking Forest, situated in the early stage of childhood, where we learn to speak, to understand the meanings of words. Poplar is a solar tree. In the Talking Forest, its time of power is August, after the seeds have scattered, during the late summer rains, when the tree speaks most clearly to us.

Talking Forest Poplar Rune